ERU - ENERGY RECOVERY UNIT

In the modern global scenario, humanity faces unprecedented challenges regarding the pursuit of sustainability, clean energy, and environmental preservation. As the impacts of climate change and environmental degradation become more evident, the need to adopt environmentally responsible practices and technologies becomes crucial. The growing awareness of the limits of finite natural resources and the consequences of greenhouse gas emissions drives the demand for sustainable alternatives in the field of energy and waste management.

In this global context, society is increasingly focused on reducing environmental footprints, promoting clean and renewable energy sources, and implementing innovative solutions to address environmental challenges. The transition to a greener and more sustainable economy is a priority in many countries, recognizing the relationship between environmental preservation, human well-being, and economic progress.

The city of Santos and the broader Baixada Santista region in São Paulo state face a growing problem related to the accumulation of solid waste. Due to its coastal location, dynamic economy, and dense population, the region deals with significant challenges in the proper management of urban and industrial waste. The increase in waste production, lack of efficient recycling infrastructure, and improper waste disposal have contributed to worsening this issue, resulting in environmental, social, and public health consequences. In this context, it is essential to effectively address the problem of solid waste accumulation to promote a healthier and more sustainable environment in Baixada Santista.

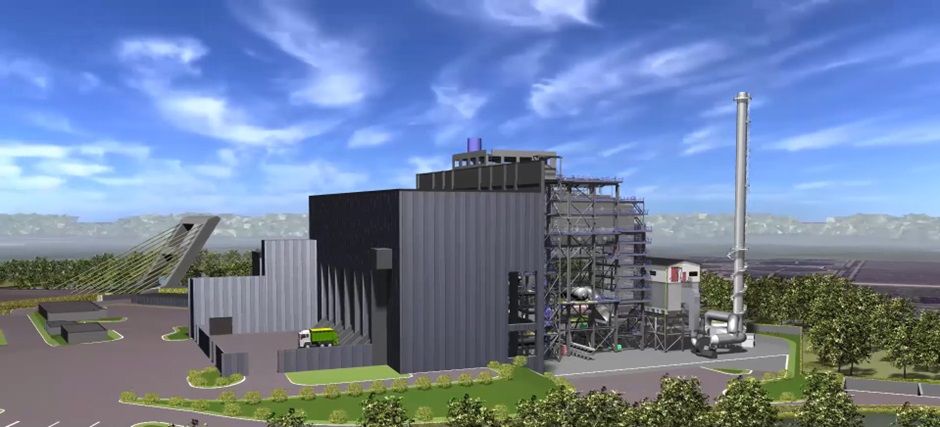

Within this scenario emerges the possibility of creating Energy Recovery Facilities (ERFs), whose basic operation consists of controlled waste incineration, where the generated heat is converted into thermal energy. This thermal energy can then be converted into electricity or used directly as heat for industrial processes, building heating, or even steam production in plants. These facilities can serve as a bridge between waste management and energy production, utilizing the energy value contained in urban and industrial solid waste that would normally be sent to landfills.

Although concerns about dioxin pollution and other heavy metals from incinerators arose in the past, advances in pollution control technology have helped mitigate these concerns to some extent. This technology is already widely used in Asia and Europe, with Japan standing out as having over 1,000 incinerators spread throughout the country.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

To better understand Energy Recovery Facilities (ERFs), we first need to understand their utility and main purposes. It's important to mention that this technology is widely used for effective waste management, which, among other terms, consists of ways to reuse the waste that society generates. According to McDougall et al. (2001), waste is a byproduct of human activity, containing materials similar to useful products but lacking value due to their mixed composition.

As societies progressed economically, becoming more industrialized with increased consumption rates and quality of life, the generation of this waste began to become a problem not only for industry but also for urban waste, creating the need to find ways not only to reduce waste generation but also to reuse it whenever possible, promoting greater sustainability for the planet.

We can define sustainable waste management as:

"Solid waste management systems must ensure human health and safety. They must be safe for workers and safeguard public health by preventing the spread of diseases. Moreover, according to these prerequisites, a sustainable solid waste management system must be environmentally effective, economically affordable, and socially acceptable." (McDougall et al., 2001, p. 18)

Now that we understand the rationale for using ERFs, we need to conceptualize them. According to Klinghoffer and Castaldi (2013), addressing energy and waste challenges requires optimized atomic economy, prioritizing understanding of the underlying processes of these issues. One approach to dealing with these challenges is ERFs, which process waste in the following manner:

"thermally converting them in specially designed chambers at high temperatures, thereby reducing them to one-tenth of their original volume while simultaneously recovering materials and energy. The heat generated by combustion or gasification is transferred to steam, which flows through a turbine to generate electricity." (Klinghoffer and Castaldi, 2013, p. 4)

METHODOLOGY

The purpose of this article is to provide a comprehensive understanding of Energy Recovery Facilities (ERFs), highlighting their definition, purpose, and potential benefits associated with their implementation in the Baixada Santista region. The research aims to analyze and emphasize the environmental and social advantages associated with implementing these facilities. In doing so, it intends to provide a theoretical foundation related to adopting this technology.

Being exploratory in nature, the article aims to increase familiarity with the topic to make it more explicit or to develop hypotheses about the chosen subject. According to Gil (2008), "These researches primarily aim to refine ideas or discover insights. Their planning is therefore quite flexible, allowing consideration of the most varied aspects related to the studied fact."

As this is an introductory approach, the method used will be bibliographic research, that is, utilizing existing sources or materials such as books, publications, articles, or texts extracted from the internet as the basis for the topic in question.

GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL CHALLENGES

As global economic growth expanded in recent decades, quality of life and consumption worldwide also increased significantly. However, this economic progress and increased consumption led to a considerable rise in waste generation. This increase in waste production represented a growing challenge for environmental management and public health worldwide.

Economic growth often translates into greater industrial production, consumption of goods and services, resulting in more packaging, disposables, and obsolete products. Consequently, the amount of waste generated has increased significantly. Increased consumption has also led to rapid product obsolescence, resulting in constant generation of electronic equipment and other short-lived items.

In the past, waste management often involved disposal in landfills, improper dumping sites, and even pollution of rivers and oceans. These often incorrect practices had serious environmental impacts, including soil and water contamination, as well as damage to biodiversity. As society became more aware of the negative environmental impacts caused by waste generation and improper disposal, concern grew.

Pollution, environmental degradation, and risks to human health triggered a global alert, and society began paying more attention to the issue, with mobilization becoming noticeable, especially from more developed countries.

Key measures to curb waste generation include:

Strict regulations and policies implemented on the issue

Recycling

Awareness campaigns about waste disposal and reduction

The circular economy, which has gained prominence by promoting material and product reuse while minimizing waste

Innovative technological solutions for more sustainable approaches

Among these innovations are ERFs, which, as mentioned earlier, emerged as a sustainable alternative to generate energy from waste.

EUROPEAN CONTEXT

One of the main factors that led to the construction of ERFs in Europe was growing concern about waste management. The constant increase in urban and industrial waste production presented a challenge regarding limited space available for conventional landfills. This required seeking alternatives that would allow more effective waste management.

The search for clean and sustainable energy sources was also a key factor. With growing environmental concerns and the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, ERFs were recognized as a way to generate energy from waste, contributing to sustainability goals.

The idea of a circular economy, where resources are used efficiently and waste is minimized, gained prominence. ERFs aligned with this model by recovering energy from waste, thereby reducing the need for new raw materials.

In the 1990s, countries like Sweden, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, and Norway had already built and continued to invest in incineration plants as one solution to waste management challenges while seeking to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and generate clean energy from waste.

Moreover, stricter environmental regulations and policies played an important role in promoting ERFs. Perhaps the most significant was the 1999 Landfill Directive, officially known as "Directive 1999/31/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on the landfill of waste," which aimed to regulate waste disposal in landfills across Europe. This directive responded to environmental challenges and the need to promote more sustainable waste management throughout the EU.

One of the main implications of this directive was increased demand for waste management alternatives, including incineration. This occurred due to the reduction in the amount of waste allowed in landfills as stipulated by the directive. With less waste going to landfills, incineration plants became a more attractive option.

According to European Council data, from 1995 to 2021 there was an estimated 106% increase in incinerated waste, rising from 30 to 62 million tons of waste, while landfill operations decreased from 121 to 54 million tons, representing a 56% decline.

One of the main roles played by incineration plants after the directive's implementation was energy recovery from waste. The heat generated by the incineration process began to be converted into electricity or used for heating, making incineration a sustainable alternative.

Currently, however, there are debates about these plants' environmental effects. Waste incinerators can have various negative impacts that must be considered when assessing the viability and public acceptance of these facilities. During the incineration process, facilities release air pollutants, including sulfur dioxide (SO₂), nitrogen oxides (NOₓ), carbon monoxide (CO), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and fine particulates. These emissions can harm air quality and public health, especially if facilities lack adequate pollution control systems.

Another concern is the generation of dioxins and furans, highly toxic organic compounds, during incineration. Exposure to these substances can have significant impacts on human health and the environment. Additionally, incineration generates ash residue that often contains heavy metals and other pollutants. Improper disposal of this ash can pose environmental risks.

Both construction and operation of incinerators consume natural resources and energy, which may conflict with sustainability principles. Furthermore, incineration can transform hazardous waste into ash and gaseous emissions, making safe treatment and disposal of this waste more difficult.

Public acceptance of incinerator construction often faces resistance from local communities, who raise concerns about health, the environment, and air quality. Some argue that incineration may discourage recycling and waste reduction practices, as it can be seen as an easier alternative for waste disposal. Additionally, incinerators emit carbon dioxide (CO₂) and other greenhouse gases, which may impact climate change, depending on the efficiency and technology used.

It's important to highlight that the European Union has adopted ambitious targets regarding waste recycling and landfill treatment. The goal is to promote a shift toward a more sustainable model known as the circular economy. One of these objectives is to have all municipal waste at a 60% recycling or reuse rate by 2030.

Within this scenario, it becomes primary to analyze individual countries' practices, where we can highlight Germany, Bulgaria, Austria, and Slovenia, which have already reached or exceeded this 60% target, while landfill disposal in these countries represents less than 10% of the total amount of waste sent, with the remainder going to energy recovery facilities.

ASIAN CONTEXT

The waste-to-energy (WtE) market has grown considerably since incineration began in 1874. Large markets were established in Europe as well as parts of Asia. However, concerns about harmful byproducts from the incineration process, both related to pollution and public health, led to widespread regulatory tightening of dioxin, particulate, and fuel emissions.

In Asia, fossil fuels are still widely used, with coal being the largest source, accounting for 52% of the electricity mix, followed by natural gas and hydropower. Today, no Asian country depends on modern renewable energy (solar and wind) or nuclear as its main electricity source. However, these clean energy sources have doubled in the last decade and are accelerating. Asia was most responsible for all-time high energy generation-related emissions last year. Yet energy transition ambitions will cause emissions to fall after 2025.

China already treats 55% of its waste with energy recovery plants, according to 2022 data from consultancy Ecoprog. There are 2,596 WtE plants worldwide, with 622 in China, processing 229 million tons per year of municipal solid waste.

According to Ecoprog's 2020 report, China leads the ranking of countries with the highest installed capacity for energy recovery from waste through thermal treatment, with capacity to process 170 million tons per year of solid waste. Following are Japan with 65 million tons/year, the United States with 29 million tons/year, and Germany with capacity to treat 27 million tons/year. Continentally, Asia leads with 66% of global waste-to-energy capacity, followed by Europe with 26%, and North America with 8%.

Japan was one of the first countries in the world to recognize the need to measure efforts to properly treat waste, especially industrial waste, after the country underwent major technological expansion in the 1950s and 1960s that generated solid positive impacts on the country's economy at the cost of environmental neglect. Industrial effluents, soot, and smoke caused pollution, affecting the environment and harming residents' health. The amount of waste generated by industry increased drastically, and to reduce these damages, the government began encouraging through subsidies the construction of waste incineration plants (at that time still without conversion technology), as an alternative to local landfills, with the first such plant built to operate in 1963.

In the 1970s and 1980s, problems continued to increase, especially regarding illegal waste dumping. It was then that the country began taking measures to properly treat industrial waste. Many environmental laws were created during this period, notably the Waste Management and Public Cleansing Law, which basically aimed to promote separation between "industrial waste" and "municipal solid waste." Rigorous standards were applied to industrial waste to ensure proper treatment. However, these regulations did not have the desired effect due to the constant increase in waste generation, making it clear that unless the social structure based on mass production, mass consumption, and mass disposal was changed, other measures would need to be taken.

Over time and with continued efforts to combat these situations, technologies evolved to the same level as in Europe, and by the late 1990s Japan began showing promising results in waste management. The plants, already completely widespread throughout the national territory and capable of converting waste into energy, became an important factor in the decline of impacts caused by increasing waste generation.

Something that makes Japan unique in its relationship with these plants is how waste ends up becoming energy. Unlike conventional plants that use incineration to convert waste into energy, the East Asian country sought another way to convert waste to energy: gasification. As a densely populated area, both landfills and conventional incinerators would generate even more aggravating environmental risks in Japan than in other countries like China and some in Europe.

Also in Asia, we can highlight that as Southeast Asian countries have experienced rapid economic growth, infrastructure development, and urbanization, as usual waste generation has increased, and nations have increasingly been implementing their know-how in ERFs together with companies to combat the environmental challenges this growth ends up causing.

A waste incineration plant in Tuas district, southwestern Singapore, can process about 35% of the waste the city-state generates daily. Some 500 to 600 garbage trucks transport waste continuously to the plant, whose energy production capacity reaches 120 megawatts.

While incineration emits carbon dioxide, landfills generate methane gas, which is 25 times more potent as a greenhouse gas. The shift to incineration reduces the amount of landfilled waste and the environmental effect, according to Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Environmental and Chemical Engineering.

Waste-to-energy plants can also generate electricity using heat produced during incineration, leading to rapidly growing interest in Southeast Asia.

BRAZILIAN AND BAIXADA SANTISTA SCENARIO

In the Brazilian scenario, unlike contexts like Europe and Asia (mostly first-world countries that have adopted this practice for some time), we must consider certain challenges that may arise when adapting the technology to our environment. Brazil still lacks adequate infrastructure for the treatment and disposal of municipal solid waste. The construction and development of ERFs require considerable investments in infrastructure, advanced incineration equipment, pollution control systems, among others. These initial costs can be a significant burden for public authorities or private companies seeking to establish these facilities.

The country also faces challenges related to the lack of clear policies and regulations on waste and recycling. The absence of solid guidelines can hinder the development of ERF projects. Another aggravating factor in this situation is the relationship between waste management and recycling, since indiscriminate waste incineration could result in unproductive habits from the perspective of recycling and circular economy for society. The ideal alternative to this problem would be to find ways to educate the population about the benefits of recycling as a whole, but considering Brazil's history in this matter and the condition that an awareness program would take years to begin showing promising results, this alternative might take too long for the required timeframe to solve the presented issue.

Another interesting factor to note, from a social perspective, is that with a relevant population below the poverty line, Energy Recovery Facilities face a significant challenge directly related to recycling workers. This occurs because the main heat source used by ERFs consists of materials with high calorific potential, such as paper, cardboard, and plastic. These materials are also of great interest to waste pickers, who collect and recover these items, generating income for thousands of families.

With all these factors established, the creation of ERFs in Brazil ends up becoming a notable challenge due to its economic, social, and environmental implications. These factors were decisive for the suspension of the waste licensing proposal that was debated for the city of Santos some years ago. The city, which has an overloaded municipal landfill, has still not managed to find and put into operation new ideas to resolve concerns about waste generation in the city. Considering the region's economic importance and its densely populated area, it is vitally important that new solutions be found for better waste management not only in the city but in the region as a whole.

While many arguments against using the technology on Brazilian soil are still being debated and evaluated, Brazil is preparing to have its first energy recovery plant (ERF) with expected operation starting in 2025, located in Barueri, São Paulo, with 20 MW of installed capacity.

CONCLUSION

The current global scenario drives the search for solutions that promote sustainability, clean energy, and environmental preservation. In this context, Energy Recovery Facilities (ERFs) emerge as a promising alternative for solid waste management, especially in densely populated regions like Baixada Santista. These facilities offer the ability to transform waste into a clean energy source, reducing the amount of material sent to landfills and mitigating the negative environmental impacts associated with this practice.

However, the adoption of ERFs in Brazil faces significant challenges, such as lack of adequate infrastructure, absence of clear policies and regulations on waste and recycling, and concerns about the impact the plants may have on recyclable material collection. Moreover, the financial costs of constructing and maintaining ERFs can be substantial.

The experience of European and Asian countries demonstrates the potential benefits of these facilities in terms of reducing landfill-bound waste, generating clean energy, and contributing to the circular economy. However, it is crucial to consider environmental impacts, such as pollutant emissions and management of incineration residues.

In summary, ERFs have the potential to be a key component in the pursuit of more effective waste management and the transition to a greener, more sustainable economy. It is essential, however, to address the specific challenges of the Brazilian context, recognizing the importance of public awareness, support from appropriate policies and regulations, and the development of practices that allow ERFs to coexist with more sustainable activities like recycling. The successful implementation of ERFs combined with other waste management methods could not only solve waste management problems but also contribute significantly to the pursuit of a more sustainable and environmentally responsible future.